Publishing Under Fire: The Nippon Fijii and the Aftermath of Pearl Harbor…

December 8, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

It’s difficult to fathom what it must have been like to be a Japanese-American living in Hawaii at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack. According to the 1940 census, more than 150,000 Japanese-Americans—roughly 35% of Hawaii’s population—suddenly found themselves in an impossible position, caught between loyalty to their home and suspicion from their neighbors.

Fear quickly swept through the islands. While the sheer size of the Japanese-American community made mass internment in Hawaii unfeasible, more than 2,000 individuals were arrested, many later sent to internment camps on the mainland. Their lives—and their trust in the nation they called home—were forever changed.

It was in the midst of this uncertainty and fear that the staff of NIPPON FIJI, Hawaii’s leading Japanese-language newspaper, produced their December 8, 1941 issue. The paper stands today as one of the most striking and rare firsthand publications from that dark and defining moment in American history.

The December, 2025 Catalog (#361): Must-Have Newspapers for the 250th Anniversary of American Independence (1776–2026)

December 6, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

As the United States approaches its semiquincentennial in 2026, collectors, museums, and history lovers are hunting for the most evocative newspapers from the Revolutionary era. This month’s RareNewspapers.com catalog is packed with exactly those treasures—original issues that let you hold the birth of the nation in your hands. Here are the top standouts that speak directly to the 250th anniversary celebration:

As the United States approaches its semiquincentennial in 2026, collectors, museums, and history lovers are hunting for the most evocative newspapers from the Revolutionary era. This month’s RareNewspapers.com catalog is packed with exactly those treasures—original issues that let you hold the birth of the nation in your hands. Here are the top standouts that speak directly to the 250th anniversary celebration:

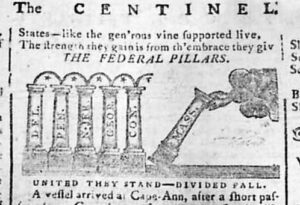

1. #703265 – Massachusetts Centinel, Boston, January 16, 1788 – $5,885

The iconic “Federal Edifice” pillar cartoon showing the 11 ratified states holding up the new Constitution. One of the most famous visual celebrations of the successful Revolution and the founding of the permanent United States government.

2. #687284 – Norwich Packet, Connecticut, December 18, 1783 – $4,275

George Washington’s emotional farewell to his officers at Fraunces Tavern – the moment the Commander-in-Chief resigned his commission and returned power to the people. A perfect “end of the Revolution” companion piece for 2026 displays.

3. #718898 – The Cape-Fear Mercury, Wilmington, North Carolina, June 3, 1775 – $3,995

A rare (and intriguingly forged) Southern colonial newspaper from just weeks after Lexington & Concord. One of the scarcest North Carolina titles from the fateful year 1775.

4. #703479 – The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, August 2, 1753 – $3,925

With Benjamin Franklin’s own imprint in the masthead. Franklin, the ultimate Founding Father, printed this very newspaper—making it an ideal pre-Revolutionary artifact leading into the 250th.

5. #703307 – Connecticut Courant, Hartford, February 10, 1777 – $1,485

Prints more than half of Thomas Paine’s legendary “American Crisis” Number 2 (“These are the times that try men’s souls…”). Paine’s words kept the Revolution alive during its darkest winter.

6. #703299 – New-England Chronicle, Cambridge, January 4, 1776 – $895

Major General Charles Lee’s fiery open letter to British General Burgoyne, plus the exposure of Dr. Benjamin Church’s traitorous letter to the British—the first known act of American espionage.

7. #701110 – Boston Gazette & Country Journal, July 9, 1770 – $975

Paul Revere’s famous patriotic masthead engraving of Liberty releasing the dove of peace, combined with fiery coverage of the Non-Importation Agreement in the wake of the Boston Massacre. Pure 1770 resistance spirit.

Also noteworthy in the Revolutionary-era spotlight this month:

• The definitive three-day Battle of Gettysburg coverage is stunning (#705943), but for the 250th focus, the issues above are the true headliners.

If you or your institution are building a 2026 exhibit, creating a museum-quality timeline, or simply want to own the actual newsprint read by Patriots 250 years ago, what remains from the above are viewable HERE.

Which one will be the centerpiece of your America 250 collection? Let us know in the comments!

Lead-up to a Nation… as reported in the newspapers of the day (November, 1775)…

December 5, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

Continental Currency – No Power to Tax or Regulate (Lead-up to a Nation – E14)

League of Friendship-Articles of Confederation Underscored National Power (Lead-up to a Nation-E15)

James Rivington – From Impartial to Loyalist (Lead-up to a Nation – E16)

The Liberty Bell – Proclaim Liberty Through the Land (Lead-up to a Nation – E17)

We hope you are enjoying this year-long trek to the 250th anniversary of The United States through the eyes of those who were fully engaged, first hand. As mentioned previously, all accounts are rooted in what they read in the newspapers of the day.

“History is never more fascinating than when read from the day it was first reported.” (Timothy Hughes, 1975)

Announcing: Catalog #361 for December, 2025 – Rare & Early Newspapers…

December 1, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

|

|

Properly Directed Thankfulness – George Washington and the Foundations of a New Nation…

November 25, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

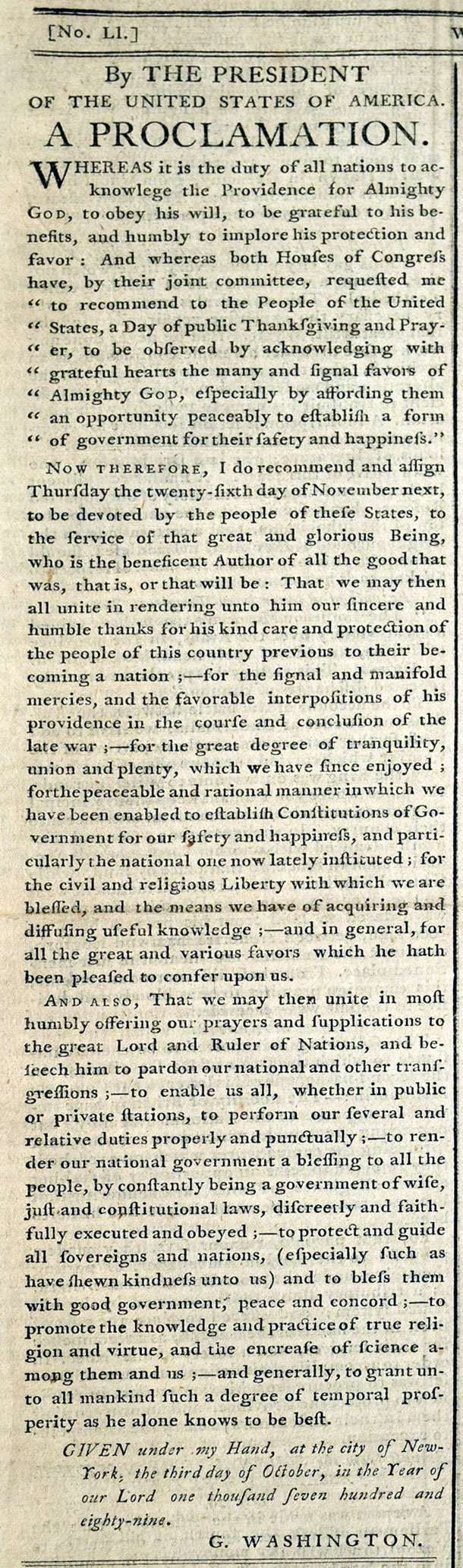

On October 3, 1789, just months into his presidency, George Washington issued the very first official presidential proclamation. Fittingly, his choice of subject set the tone for a new nation: a call for a national day of thanksgiving and prayer. In it, Washington urged the people of the United States to acknowledge “with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.” This was more than a holiday declaration—it was a reminder that gratitude, humility, and faith would form part of the nation’s foundation.

Below is the complete text of Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamation as it appeared on the front page of the Gazette of the United States on October 7, 1789:

From the Vault: The top ten: “20th century”…

November 21, 2025 by TimHughes · 9 Comments

From this period in newspaper publishing history, displayability has much to do with the desirability of a newspaper, perhaps more so than historical significance. Since I come to this task of listing the “top ten” from the perspective of a rare newspaper dealer and knowing the requests we receive for certain events, the following list may not be the same as my most “historic” but they are my thoughts for the most “desirable” based on customer demand. Certainly FDR’s New Deal is more historically significant than the death of Bonnie & Clyde, but not more desirable from a collector standpoint. I’d be curious to hear of your thoughts.

Here they are, beginning with number ten:

Here they are, beginning with number ten:

10) St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, Feb. 14, 1929 An issue with a dramatic banner headline, & ideally dated the 14th. Morning papers would be dated the 15th.

9) Death of Bonnie & Clyde, May 23, 1934 The gangster era remains much in demand, & perhaps due to the movie this event beats out Dillinger, Capone & the others from the era. A dramatic headline drives desirability–ideally with a photo–even if not in a Louisiana newspaper.

8.) Charles Lindbergh flies the Atlantic, May 22, 1927 The New York Times had a nice headline account with a map of the route, and the prestige of the newspaper always keeps it in high demand.

7) Call-Chronicle-Examiner, San Francisco, April 19, 1906 I note a specific title & date for this event, as these 3 newspapers combined to produce one 4 page newspaper filled with banner heads & the latest news. No advertisements.

7) Call-Chronicle-Examiner, San Francisco, April 19, 1906 I note a specific title & date for this event, as these 3 newspapers combined to produce one 4 page newspaper filled with banner heads & the latest news. No advertisements.

6) Crash of the Hindenberg, May 6, 1937 The more dramatic the headline the better, & ideally with the Pulitizer Prize winning photo of the airship in flames.

5) Wright brothers fly, Dec. 17, 1903 Here’s where the significance of the event drives desirability over dramatic appeal. Few can argue the impact of manned flight on the world. Reports were typically brief & buried on an inside page with a small headline, so a lengthy front page report would be in top demand.

4) Stock market crash, October, 1929 Demand is driven by the dramatic headline and its wording. Too many newspapers tried to put an optimistic spin on the tragedy. Collectors want “collapse, disaster, crash” & similarly tragic words in the headline (how about Variety magazine’s: “Wall Street Lays On Egg”?)

3) Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Dec. 7, 1941 “1st Extra” The defining issue from World War II but be careful of reprints as most issues on the market are not genuine.

3) Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Dec. 7, 1941 “1st Extra” The defining issue from World War II but be careful of reprints as most issues on the market are not genuine.

2) Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 3, 1948 “Dewey Defeats Truman”. What more need be said?

1) Titanic sinking, April 14, 1912 Certainly low on the historically significant list, but off the charts on the desirability scale, much due to the block-busting movie. The more dramatic the headline the better, and hopefully with a nice illustration of the ship going down.

My “honorable mention” list might include baseball’s “Black Sox” scandal of 1919, sinking of the Lusitania, end of World War II, D-Day, JFK’s election, the New Deal, a great Babe Ruth issue, etc. Maybe they would rank higher on your list. Feel free to share your top choices.

Great Headlines Speak for Themselves… The First Moon Walk…

November 17, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

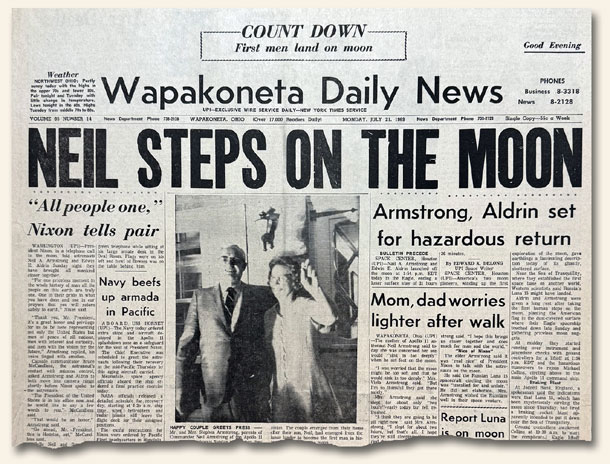

The best headlines need no commentary. Such is the case with the WAPAKONETA DAILY NEWS, Ohio, July 21, 1969, which reported the first moon walk. Whereas most newspapers declared some variation of: “Man Walks on the Moon”, this one was a little more specific – perhaps because it was his hometown newspaper:

“NEIL STEPS ON THE MOON”

Lead-up to a Nation… as reported in the newspapers of the day (October, 1775)…

November 6, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

England Misses the Temper of the Times (Lead-up to a Nation – E9)

George Washington – Religious Freedom (Lead-up to a Nation – E10)

Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys (Lead-up to a Nation – E11)

The Liberty Tree (Lead-up to a Nation – E12)

George Washington – Integrity, Leadership & Humility (Lead-up to a Nation – E13)

We hope you are enjoying this year-long trek to the 250th anniversary of The United States through the eyes of those who were fully engaged, first hand. As mentioned previously, all accounts are rooted in what they read in the newspapers of the day.

“History is never more fascinating than when read from the day it was first reported.” (Timothy Hughes, 1975)

The reason I collected it: the Nuremberg trials…

November 3, 2025 by TimHughes · Leave a Comment

I have likely stated several times that part of the quest in seeking the best report of a notable event is to find it in a newspaper as close to where it happened as possible. For the death of JFK, a Dallas newspaper is best. On the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a Honolulu newspaper is great. On the Boston Massacre in 1770, a Boston paper would be wonderful.

Some events can be extremely difficult, so you do the best you can. How about when man walked on the moon? Outside of a lunar publication that did not exist, a newspaper from Neil Armstrong’s hometown is pretty good. Or perhaps one from close to Cape Canaveral.

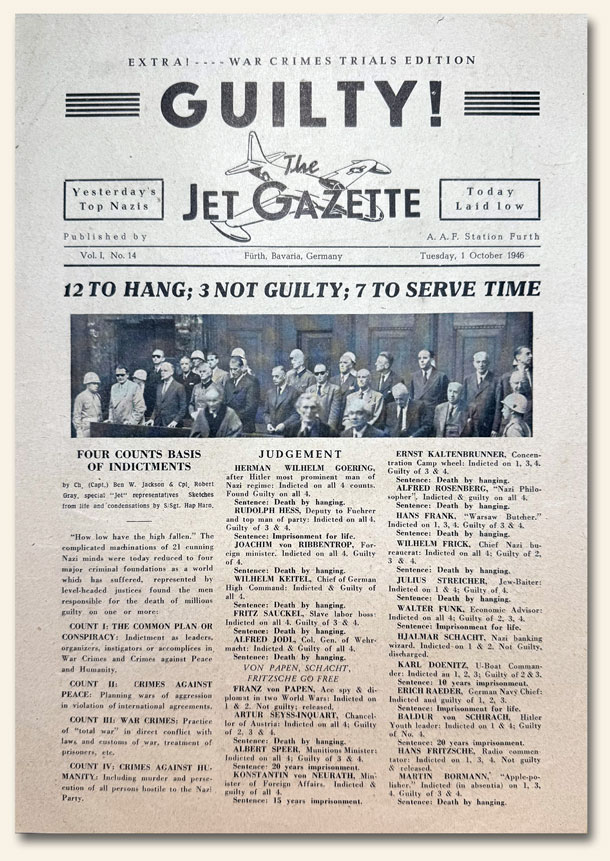

One of the more notable events at the conclusion of World War II was the Nuremberg Trials. There were 22 defendants held for war crimes; 12 would hang, 7 served time, and 3 found not guilty.

But finding a German newspaper with this report had eluded us. And as is the case with events in foreign language countries, a report close to the event would be diminished a bit if the text is in a language other than English. Not many desire a newspaper they cannot read.

But as luck would have it, a Nuremberg suburb–Furth–had a former Nazi air base, captured by American forces in early April, 1945 & converted to a U.S. air base. And better yet, it produced a small, obviously low-circulation newspaper called “The Jet Gazette”. The October 1, 1946 issue was devoted to the results of the trials. And being an American air base, it’s in English. It was a great find that I suspected never existed!

Announcing: Catalog #360 for November, 2025 – Rare & Early Newspapers…

October 31, 2025 by GuyHeilenman · Leave a Comment

|

|

Catalog #360 (for November)

Catalog #360 (for November)